SEOUL, South Korea — Of all the fantastic tales to come out of North Korea — the country’s leader is injected with the blood of virgin girls, he made 11 holes-in-one during his very first round of golf, each grain of rice he eats is inspected by hand for imperfections, his youngest son and would-be successor has had cosmetic surgery to make him resemble his grandfather — not one of these seems as improbable as the event that took place on Monday, when a science university founded by American evangelical scholars began its first day of classes in Pyongyang, the capital of the secretive Communist state.

North Korea, the nuclear-armed “hermit kingdom,” is so poor that there is almost no supply of concrete, bricks or window glass. People suffer shortages of rice, gasoline and even underwear. The Internet barely exists, not to mention computers, and the economy is so moribund that most factories barely function for lack of raw materials and electricity.

In spite of all this, classes in technical English started Monday at the Pyongyang University of Science and Technology. A fuller curriculum in information technology, business management and agriculture is supposed to get under way in March.

“It’s amazing, and kind of a miracle,” said Park Chan-mo, one of the founders of the school, which was largely financed by contributions from evangelical Christian groups in the United States and South Korea. “Many people were skeptical, but we’re all Christians. We had faith.”

The driving force behind the school was Kim Chin-kyung, an American born in Seoul who founded a university in China in 1992. He made periodic trips from China into North Korea and in 1998 was arrested at his hotel in the capital and thrown into prison, accused of being an agent for the C.I.A.

| Korean Future according to the theory of divination based on topography | |

| Moon and the Washington Times: THE ROLE IN ENDING THE COLD WAR | |

| Nostradamus, the Korean Prophecy and the Bible |

The relentless interrogations went on for six weeks and almost broke him. “I was ready to die,” he said in a 2001 interview, even writing out a will and bequeathing his organs for transplants and medical study in Pyongyang.

He was finally released, he said, after convincing the authorities that “I was not the kind of person who would spy on them.”

In November 2000, a man appeared in his university office in China — oddly, the same man who had ordered his arrest for espionage in Pyongyang in 1998. But this time he had a proposal from the North Korean government: could he duplicate his Chinese technical university in Pyongyang?

“Doing business with North Korea is not for the faint of heart,” Mr. Kim said on the school’s Web site, “but the effort is ennobling and necessary.”

The first group of 160 undergraduate and master’s students has been chosen by the North Korean government, selected from its top colleges and from the political and military elite. Their tuition, room, board and books are all free, financed by foreign donors and individual sponsors. The plans call for an eventual student body of 2,600 and a faculty of 250, with classes in public health, architecture, engineering and construction.

Sixteen professors from the United States and Europe arrived in Pyongyang over the weekend. For now, no South Korean professors are allowed because of recent political tensions between the Koreas.

It seems an unlikely marriage — the hard-line Communist state and wealthy Christian capitalists — and it remains to be seen how well the match has been made.

North Korea, while reluctant to expose its citizens to the outside world, has been seeking foreign investment for its decrepit educational system. For their part, the evangelicals, who have antagonized the North by encouraging defections and assisting refugees after they cross over, are seeking a foothold inside the churchless state.

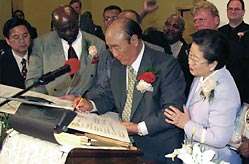

North Korea has made a similar bargain before. The Unification Church of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, not only a Christian but staunchly anti-Communist, operates a car factory in Pyongyang, for instance. But the church is allowed to make only cars, not Christians or capitalist converts.

North Korea has made a similar bargain before. The Unification Church of the Rev. Sun Myung Moon, not only a Christian but staunchly anti-Communist, operates a car factory in Pyongyang, for instance. But the church is allowed to make only cars, not Christians or capitalist converts.

There is no campus chapel at the new university, Dr. Park said, and there is not one in the plans. But neither, for now, are there any official portraits of the North Korean leader, Kim Jong-il, or his father, the late Kim Il-sung, which hang in every school and public building in the North.

The $35 million, 240-acre campus includes a faculty guesthouse and world-class dormitories and classrooms, all of which are said to have running water, power and heat. The school has its own backup generators, but with so little diesel and gasoline available in the North, fuel has to be trucked in from neighboring China.

Classes will be taught in English, and Internet access has been promised to all students. The campus has sirens that go off before rolling electrical blackouts, so work on computers can be saved.

“The Internet will be censored, and we can’t imagine that it won’t be,” said Dr. Park, who has been involved in educational exchanges with the North since 2000. “Even in South Korea things are blocked. I’m sure North Korea has been looking at my e-mails. I keep them businesslike.”

Dr. Park, the former president of the prestigious Pohang University of Science and Technology in South Korea, said the university project could not have been completed without the approval of the United States government. Officials at the school, eager not to run afoul of international sanctions in place against the North, have even sent its curriculum to the State Department for vetting.

One request from Washington was that the name of the biotechnology course be changed for fear that it might be seen as useful in developing biological weapons, Dr. Park said. So the course title was changed to “Agriculture and Life Sciences.”

The United States government also was also “very sensitive,” Dr. Park said, about young North Korean scientists learning skills that could be used by the military or in developing nuclear weapons. “We can’t be fooled into teaching them those kinds of things.”

Several conservative lawmakers from South Korea called for Seoul, which gave $1 million to the school in 2006, to cut off all support. One legislator, Yoon Sang-hyun, was angered that the North insisted that future economics classes include lessons about juche, or Kim Il-sung’s founding philosophy of self-reliance.

Some critics also have suggested that there must have been heavy payoffs made to the North Korean government to move the project along, but Mr. Kim insisted that no deals had been made.

“Every brick we used, every bit of steel, every bit of equipment, we brought in from China,” Mr. Kim, who was in Pyongyang for the opening, said in an interview in Fortune last year. “I have never brought any cash into North Korea.”

“I have unlimited credit at the Bank of Heaven,” he added.